How to Write a Winning Architecture Thesis: A Comprehensive A-Z Guide

Table of Contents

- How to Choose Your Architecture Thesis Topic

- How to Create an Area Program for your Architecture Thesis

- How to Identify Key Stakeholders for Your Architecture Thesis

- Why Empathy Mapping is Crucial for Your Architecture Thesis

- Beyond Case Studies: Component Research for your Architecture Thesis

- The Technique of Writing an Experiential Narrative for your Architecture Thesis

- Overcoming Creative Blocks During Your Architecture Thesis

- How to Prototype Form and Function During Your Architecture Thesis

- How to Convert Feedback (Crits) into Action During Your Architecture Thesis Project

- How to Structure Your Architecture Thesis Presentation for a Brilliant Jury

How to Choose Your Architecture Thesis Topic

As with most things, taking the first step is often the hardest. Choosing a topic for your architecture thesis is not just daunting but also one that your faculty will not offer much help with. To aid this annual confusion among students of architecture, we've created this resource with tips, topics to choose from, case examples, and links to further reading!

1. What You Love

Might seem like a no-brainer, but in the flurry of taking up a feasible topic, students often neglect this crucial point. Taking up a topic you're passionate about will not just make for a unique thesis, but will also ensure your dedication during tough times.

Think about the things you're interested in apart from architecture. Is it music? Sports? History? Then, look for topics that can logically incorporate these interests into your thesis. For example, I have always been invested in women's rights, and therefore I chose to design rehabilitation shelters for battered women for my thesis. My vested interest in the topic kept me going through heavy submissions and nights of demotivation!

Watch Vipanchi's video above to get insights on how she incorporated her interest in Urban Farming to create a brilliant thesis proposal, which ended up being one of the most viewed theses on the internet in India!

2. What You're Good At

You might admire, say, tensile structures, but it’s not necessary that you’re also good at designing them. Take a good look at the skills you’ve gathered over the years in architecture school- whether it be landscapes, form creation, parametric modelling- and try to incorporate one or two of them into your thesis.

It is these skills that give you an edge and make the process slightly easier.

The other way to look at this is context-based, both personal and geographical. Ask yourself the following questions:

• Do you have a unique insight into a particular town by virtue of having spent some time there?

• Do you come from a certain background, like doctors, chefs, etc? That might give you access to information not commonly available.

• Do you have a stronghold over a particular built typology?

3. What the World Needs

By now, we’ve covered two aspects of picking your topic which focus solely on you. However, your thesis will be concerned with a lot more people than you! A worthy objective to factor in is to think about what the world needs which can combine with what you want to do.

For example, say Tara loves photography, and has unique knowledge of its processes. Rather than creating a museum for cameras, she may consider a school for filmmaking or even a film studio!

Another way to look at this is to think about socio-economically relevant topics, which demonstrate their own urgency. Think disaster housing, adaptive reuse of spaces for medical care, etcetera. Browse many such categories in our resource below!

[Read: 30 Architecture Thesis Topics You Can Choose From]

4. What is Feasible

Time to get real! As your thesis is a project being conducted within the confines of an institution as well as a semester, there are certain constraints which we need to take care of:

• Site/Data Accessibility: Can you access your site? Is it possible to get your hands on site data and drawings in time?

• Size of Site and Built-up Area: Try for bigger than a residential plot, but much smaller than urban scale. The larger your site/built-up, the harder it will be to do justice to it.

• Popularity/Controversy of Topic: While there’s nothing wrong with going for a popular or controversial topic, you may find highly opinionated faculty/jury on that subject, which might hinder their ability to give unbiased feedback.

• Timeline! Only you know how productive you are, so go with a topic that suits the speed at which you work. This will help you avoid unnecessary stress during the semester.

How to Create an Area Program for your Architecture Thesis

Watch SPA Delhi Thesis Gold-Medallist Nishita Mohta talk about how to create a good quality area program.

Often assumed to be a quantitative exercise, creating an area program is just as much a qualitative effort. As Nishita says, “An area program is of good quality when all user experiences are created with thought and intention to enhance the usage of the site and social fabric.”

Essentially, your area program needs to be human-centric, wherein each component is present for a very good reason. Rigorously question the existence of every component on your program for whether it satisfies an existing need, or creates immense value for users of your site.

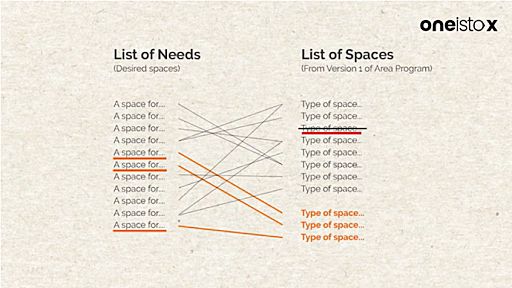

To this end, you need to create three lists:

• A list of proposed spaces by referring to area programs of similar projects;

• A list of needs of your users which can be fulfilled by spatial intervention.

• A list of existing functions offered by your immediate context.

Once you put these lists side-by-side, you’ll see that you are able to match certain needs of users to some proposed spaces on your list, or to those in the immediate context.

However, there will be some proposed spaces which do not cater to any need, and needs that are not catered to by any of the spaces. There will also be certain proposed spaces which are redundant because the context already fulfils that need.

This when you remove redundant spaces to create ones for unmatched needs, and viola, you have a good quality area program!

Confused? Here’s an example from the above video. Nishita originally intended to provide a typical eatery on her site, which she later realised was redundant because several eateries already existed around it. In this manner, she was able to fulfil the actual needs of her users- one of which was to be able to rest without having to pay for anything- rather than creating a generic, unnecessary space.

How to Identify Key Stakeholders for Your Architecture Thesis

“A stakeholder? You mean investors in my thesis?”, you scoff.

You’re not wrong! Theoretically, there are several people invested in your thesis! A stakeholder in an architectural project is anyone who has interest and gets impacted by the process or outcome of the project.

At this point, you may question why it’s important to identify your stakeholders. The stakeholders in your thesis will comprise of your user groups, and without knowing your users, you can’t know their needs or design for them!

There are usually two broad categories of stakeholders you must investigate:

• Key Stakeholders: Client and the targeted users

• Invisible Stakeholders: Residents around the site, local businesses, etc.

Within these broad categories, start by naming the kind of stakeholder. Are they residents in your site? Visitors? Workers? Low-income neighbours? Once you’ve named all of them, go ahead and interview at least one person from each category!

The reason for this activity is that you are not the all-knowing Almighty. One can never assume to know what all your users and stakeholders need, and therefore, it’s essential to understand perspectives and break assumptions by talking directly to them. This is how you come up with the aforementioned 'List of Needs', and through it, an area program with a solid footing.

An added advantage of carrying out this interviewing process is that at the end of the day, nobody, not even the jury, can question you on the relevance of a function on your site!

Why Empathy Mapping is Crucial for Your Architecture Thesis

Okay, I interviewed my stakeholders, but I can’t really convert a long conversation into actionable inputs. What do I do?

This is where empathy mapping comes in. It basically allows you to synthesize your data and reduce it to the Pain Points and Gain Points of your stakeholders, which are the inferences of all your observations.

• Pain Points: Problems and challenges that your users face, which you should try to address through design.

• Gain Points: Aspirations of your users which can be catered to through design.

In the above video, Nishita guides you through using an empathy map, so I would highly recommend our readers to watch it. The inferences through empathy mapping are what will help you create a human-centric design that is valuable to the user, the city, and the social fabric.

Download your own copy of this Empathy Map by David Gray, and get working!

Beyond Case Studies: Component Research for your Architecture Thesis

Coming to the more important aspects, it’s essential to know whether learning a new skill will expand your employability prospects. Otherwise, might as well just spend the extra time sleeping. Apart from being a highly sought-after skill within each design field, Rhinoceros is a unique software application being used across the entire spectrum of design. This vastly multiples your chances of being hired and gives you powerful versatility as a freelancer or entrepreneur. The following are some heavyweights in the design world where Rhino 3D is used:

Case Studies are usually existing projects that broadly capture the intent of your thesis. But, it’s not necessary that all components on your site will get covered in depth during your case studies.', 'Instead, we recommend also doing individual Component (or Typology) Research, especially for functions with highly technical spatial requirements.

For example, say you have proposed a residence hall which has a dining area, and therefore, a kitchen- but you have never seen an industrial kitchen before. How would you go about designing it?', 'Not very well!', 'Or, you’re designing a research institute with a chemistry lab, but you don’t know what kind of equipment they use or how a chem lab is typically laid out.

But don’t freak out, it’s not necessary that all of this research needs to be in person! You can use a mixture of primary and secondary studies to your advantage. The point of this exercise is to deeply understand each component on your site such that you face lesser obstacles while designing.

[Read: Site Analysis Categories You Need to Cover For Your Architecture Thesis Project]

The Technique of Writing an Experiential Narrative for your Architecture Thesis

A narrative? You mean writing? What does that have to do with anything?

A hell of a lot, actually! While your area programs, case studies, site analysis, etc. deal with the tangible, the experience narrative is about the intangible. It is about creating a story for what your user would experience as they walk through the space, which is communicated best in the form of text. This is done for your clarity before you start designing, to be your constant reference as to what you aim to experientially achieve through design.

At the end of the day, all your user will consciously feel is the experience of using your space, so why not have a clear idea of what we want to achieve?

This can be as long or as short as you want, it’s completely up to you! To get an example of what an experience narrative looks like, download the ebook and take a look at what Nishita wrote for her thesis.

Overcoming Creative Blocks During Your Architecture Thesis

Ah, the old enemy of the artist, the Creative Block. Much has been said about creative blocks over time, but there’s not enough guidance on how to overcome them before they send your deadline straight to hell.

When you must put your work out into the world for judgement, there is an automatic fear of judgement and failure which gets activated. It is a defensive mechanism that the brain creates to avoid potential emotional harm.

So how do we override this self-destructive mechanism?

As Nishita says, just waiting for the block to dissolve until we magically feel okay again is not always an option. Therefore, we need to address the block there and then, and to systematically seek inspiration which would help us with a creative breakthrough.

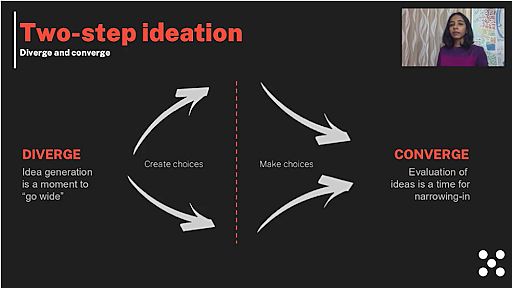

This is where the concept of Divergent and Convergent Thinking comes in.

• Divergent Thinking: Say you browse through ideas on pinterest to get inspired. If you’re in a creative rut, do just that, but don’t worry about implementing any of those ideas. Freely and carelessly jot down everything that inspires you right now regardless of how unfeasible they may be. This is called Divergent Thinking! This process will help unclog your brain and free it from anxiety.

Divergent and convergent thinking.

• Convergent Thinking: Now, using the various constraints of your architecture thesis project, keep or eliminate those ideas based on how feasible they are for your thesis. This is called Convergent Thinking. You’ll either end up with some great concepts to pursue, or have become much more receptive to creative thinking!

Feel free to use Nishita’s Idea Dashboard (example in the video) to give an identity to the ideas you chose to go forward with. Who knows, maybe your creative block will end up being what propels you forward in your ideation process!

How to Prototype Form and Function During Your Architecture Thesis

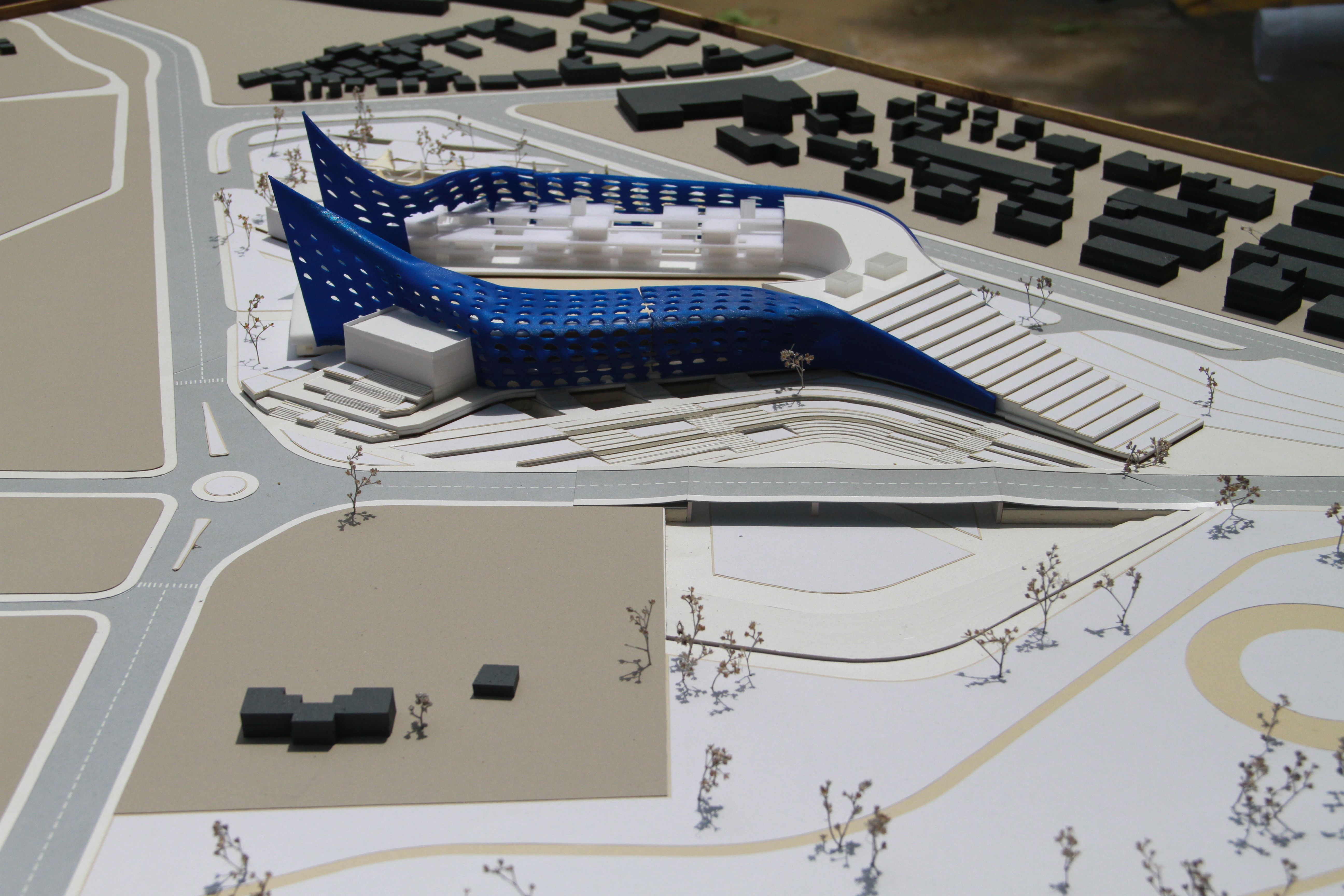

Prototyping is one of the most crucial processes of your architecture thesis project. But what exactly does it mean?

“A preliminary version of your designed space which can be used to give an idea of various aspects of your space is known as a prototype.”

As Nishita explains in the video above, there can be endless kinds of prototypes that you can explore for your thesis, and all of them explain different parts of your designed space. However, the two aspects of your thesis most crucial to communicate through prototyping are Form and Function.

As we know, nothing beats physical or 3D models as prototypes of form. But how can you prototype function? Nishita gives the example of designing a School for the Blind, wherein you can rearrange your actual studio according to principles you’re using to design for blind people. And then, make your faculty and friends walk through the space with blindfolds on! Prototyping doesn’t get better than this.

In the absence of time or a physical space, you may also explore digital walkthroughs to achieve similar results. Whatever your method may be, eventually the aim of the prototype is to give a good idea of versions of your space to your faculty, friends, or jury, such that they can offer valuable feedback. The different prototypes you create during your thesis will all end up in formulating the best possible version towards the end.

Within the spectrum of prototypes, they also may vary between Narrative Prototypes and Experiential Prototypes. Watch the video above to know where your chosen methods lie on this scale and to get more examples of fascinating prototyping!

How to Convert Feedback (Crits) into Action During Your Architecture Thesis Project

Nishita talks about how to efficiently capture feedback and convert them into actionable points during your architecture thesis process.

If you’ve understood the worth of prototyping, you would also know by now that those prototypes are only valuable if you continuously seek feedback on them. However, the process of taking architectural ‘crits’ (critique) can often be a prolonged, meandering affair and one may come out of them feeling dazed, hopeless and confused. This is especially true for the dreaded architecture thesis crits!

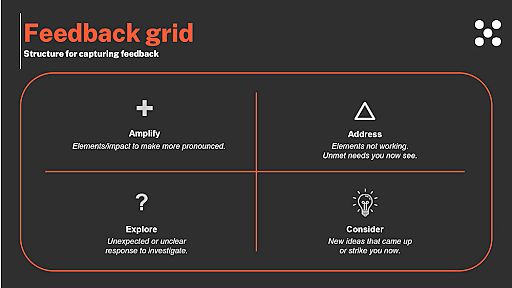

To avoid that, Nishita suggests capturing feedback efficiently in a simple grid, noting remarks under the following four categories:

• Amplify: There will be certain aspects of your thesis that your faculty and friends would appreciate, or would point out as key features of your design that must be made more prominent. For example, you may have chosen to use a certain definitive kind of window in a space, which you could be advised to use more consistently across your design. This is the kind of feedback you would put under ‘Amplify’.

• Address: More often, you will receive feedback which says, ‘this is not working’ or ‘you’ve done nothing to address this problem’. In such cases, don’t get dejected or defensive, simply note the points under the ‘Address’ column. Whether you agree with the advice or not, you cannot ignore it completely!

• Explore: Sometimes, you get feedback that is totally out of the blue or is rather unclear in its intent. Don’t ponder too long over those points during your crit at the cost of other (probably more important) aspects. Rather, write down such feedback under the ‘Explore’ column, to investigate further independently.

• Consider: When someone looks at your work, their creative and problem-solving synapses start firing as well, and they are likely to come up with ideas of their own which you may not have considered. You may or may not want to take them up, but it is a worthy effort to put them down under the ‘Consider’ column to ruminate over later!

Following this system, you would come out of the feedback session with action points already in hand! Feel free to now go get a coffee, knowing that you have everything you need to continue developing your architecture thesis project.

How to Structure Your Architecture Thesis Presentation for a Brilliant Jury

And so, together, we have reached the last stage of your architecture thesis project: The Jury. Here, I will refrain from telling you that this is the most important part of the semester, as I believe that the process of learning is a lot more valuable than the outcome. However, one cannot deny the satisfaction of a good jury at the end of a gruelling semester!

Thanks for connecting!

Thanks for connecting!

.png)